Life as play: Rethinking Kindergarten Design for a New Generation

While autumn is coming closer and with it comes the reminder of how quickly our world is changing—and how often the field of education struggles to keep up. One of the biggest challenges lies in the physical spaces themselves: many school and kindergarten buildings simply weren’t designed for today’s reality.

Take kindergartens, for example. In many cities around the world, especially in older neighborhoods, these institutions still operate in buildings constructed decades ago, according to the regulations and approaches of that time. These buildings, often guided by sanitary codes designed in another era, prioritize separation, control, and uniformity. Rows of identical sleeping rooms, closed-off group spaces, choice of color solutions, furniture – an architecture and design of order, not of inspiration. Their design reflects outdated views on child development and learning, and as a result, they no longer meet the needs of today’s children.

While these rules were intended to prevent the spread of illness, they often produced monotonous, segregated interiors. Today, educational philosophy has shifted. Psychologists and educators emphasize open-ended play, flexible spaces, and environments that support emotional as well as intellectual development. But the buildings remain locked in an older logic.

Of course, new kindergartens are being built according to new standards, but what to do with the old ones? This is where reconstruction becomes a critical tool. Instead of demolishing, architects can transform these structures, respecting regulations but reframing them through new materials, transparency, and flexibility. The task of contemporary architecture is not only to keep them safe, but to nurture their creativity and well-being.

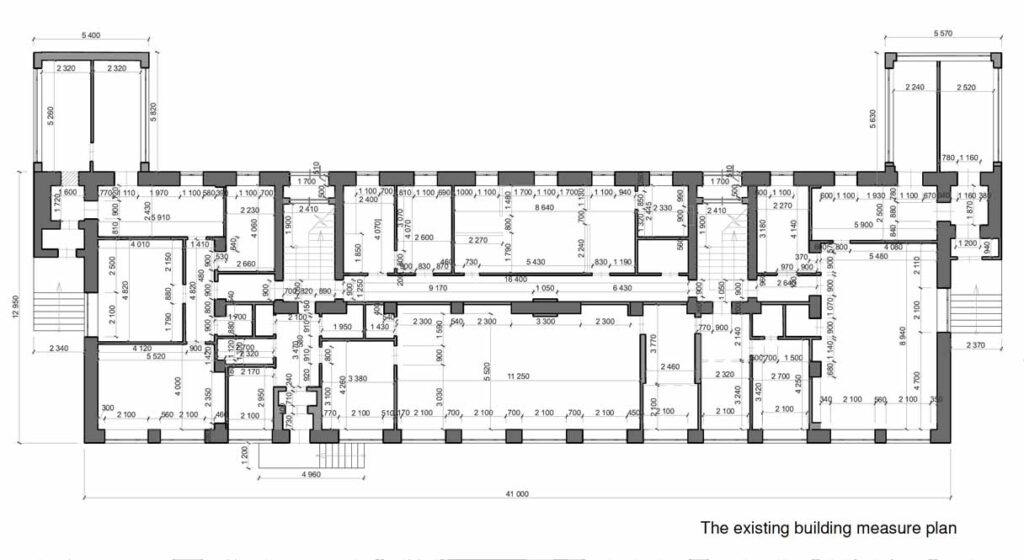

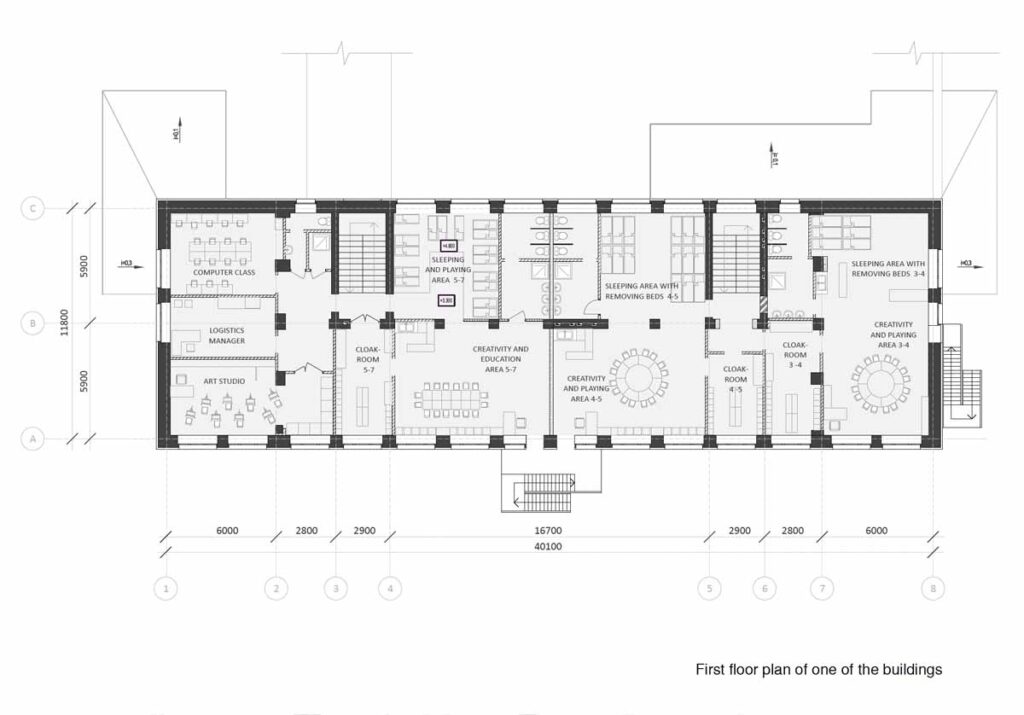

For example, let’s see how even the most typical kindergarten layout from that era can be transformed into a space of imagination and freedom in The project that won the city tender for the reconstruction of two abandoned kindergartens in Novochibirsk, Russia, developed by architect Inessa Garder. The two separate buildings were connected with a glazed gallery, uniting them into one functional whole. This clever move reduced duplication of administrative and utility zones, freeing more space for educational, recreational, and creative activities. The design team then asked: how can architecture encourage children to feel freedom, joy, and creativity, while still operating within the rigid building codes?

The architect with her team came up with a few clean solutions:

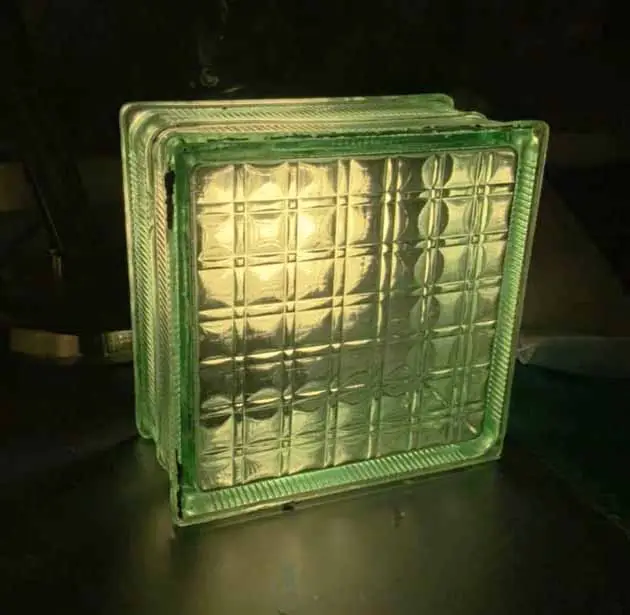

- Walls of light: instead of opaque partitions, the architect introduced glass blocks in modern colors and textures. A nostalgic material of buildings in the constructivist style, they are reborn here as luminous, modular, and playful dividers. They comply with separation rules, yet turn walls into sources of light and magical refractions

- Transformable partitions: group rooms use safe, translucent sliding panels made from shatterproof polycarbonate. Beyond simply dividing space, they invite children to draw and leave traces, turning regulation into creativity.

- Transparent storage: toys and supplies live in modular, numbered boxes that line the walls. The storage is no longer hidden away—it becomes part of the educational environment, giving children autonomy to access and organize.

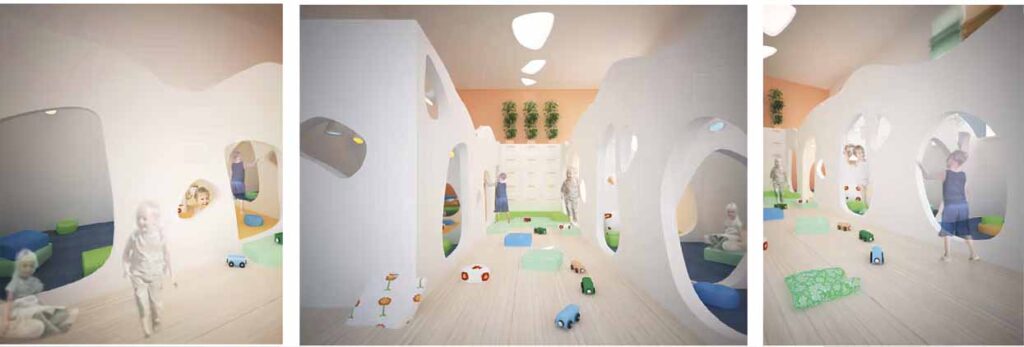

- Sleeping as landscape: the most radical intervention reimagined the bedroom. Instead of rows of identical beds, the architects designed a soft, modular landscape of cushions and platforms. Here, rest is not imposed but discovered—children may fall asleep naturally, amid play, in a space that feels warm and free.

As architect Inessa Garder reflects, the challenge was not simply to design within strict codes, but to reinterpret them: “We changed the way space itself could be experienced. Our goal was simple: to give children the freedom to feel that life is play” .

The Novosibirsk project offers a compelling model for how outdated structures can be reconstructed rather than replaced, with relatively modest interventions yielding transformative results. This philosophy reflects a broader truth: the architecture of childhood shapes not only how children learn, but how they imagine the world.

The cover and article use visualizations from the project: Architects: Inessa Garder. Project: Reconstruction of two abandoned Soviet-era kindergartens, Novosibirsk, Russia. Status: Winner of municipal competition; completed as city tender project