How Family History Influences The Interior Design

The editorial team of DI Catalogue was invited to a home shaped from within – a place where art, memory, and everyday life are deeply intertwined. This is the home of Rebecca Shore, an artist, created for her, her husband, and their family by her son, interior designer Simcha Shore. We spoke with Rebecca and Simcha about what it means to work together as mother and son, artist and designer, about trust, intuition, and about how a shared creative process can transform not only a space, but the way a family lives within it.

Rebecca, can you take us back to the very beginning? How did you find this house, and what made you see potential in it?

We were living in the Old City of Jerusalem, in a very old house, around 500 years old, with domed ceilings. It was long and narrow, room after room. About ten years ago I felt I needed a change. The community had changed, and I wanted something different, but still within walking distance from the Jerusalem Old City because we observe Shabbat.

I’ve always loved this neighborhood. I don’t know why, but it pulled me. I noticed one realtor who kept listing houses here, so I called him. He was on his way to a family vacation, but after I described what I was looking for, he said, “I think I might have something.” When he brought me here, it was love at first sight, especially the porch. The house itself was in a terrible condition. Twenty-five years of students living here, no maintenance at all. Graffiti on the walls, a disgusting kitchen, a very gross bathroom. Most people would have walked out.

Simcha wasn’t involved at that point, he was in Toronto studying interior design. But I’m an artist. In my head, I took down all the walls immediately. I saw the windows, the light. This is an Ottoman house dating back to 1917, just before the British Mandate period. I already had a vision: rip everything out and start again.

The house has a strong historical layer. How did that affect the renovation process?

Rebecca: Very much. After 1948, this area became a border zone, a no-man’s-land. There were snipers here. The neighbouring house still has bullet holes in its doors. This house was turned into a kind of refugee space: five families living on one floor, one family per room. No proper bathrooms, no kitchen. Over time, the house became a dormitory. Almost none of the original iterior survived. Some floors were gone, laminate was glued over others. We kept whatever we could. For example, the front door is original, one window upstairs, and the general proportions. Because it’s a historica house, the Jerusalem preservation department supervised everything. We were allowed to enlarge some windows and add new ones, but only if they matched the original language.

What was it like to work together as mother and son?

Simcha: Working with family actually made it easier. My mom knows what she wants, especially with color. She gave me a lot of freedom with details. And because they’re my parents, we could move in before everything was finished. That’s a privilege designers usually don’t have.

Rebecca: From an aesthetic perspective, it was easy. We’re very aligned. I’m a big-picture person, especially with color, and Simcha is incredible with detail. He’s an optimizer. He sees solutions I would never see.

Simcha, at what stage did you enter the process?

I came in after the house was purchased. Just buying it took almost a year. There were six inheritors, negotiations over roof rights – we owned 60%, the neighbors 40%. Then three and a half years just to get building permits. By the time construction started, we had gone through many design iterations.

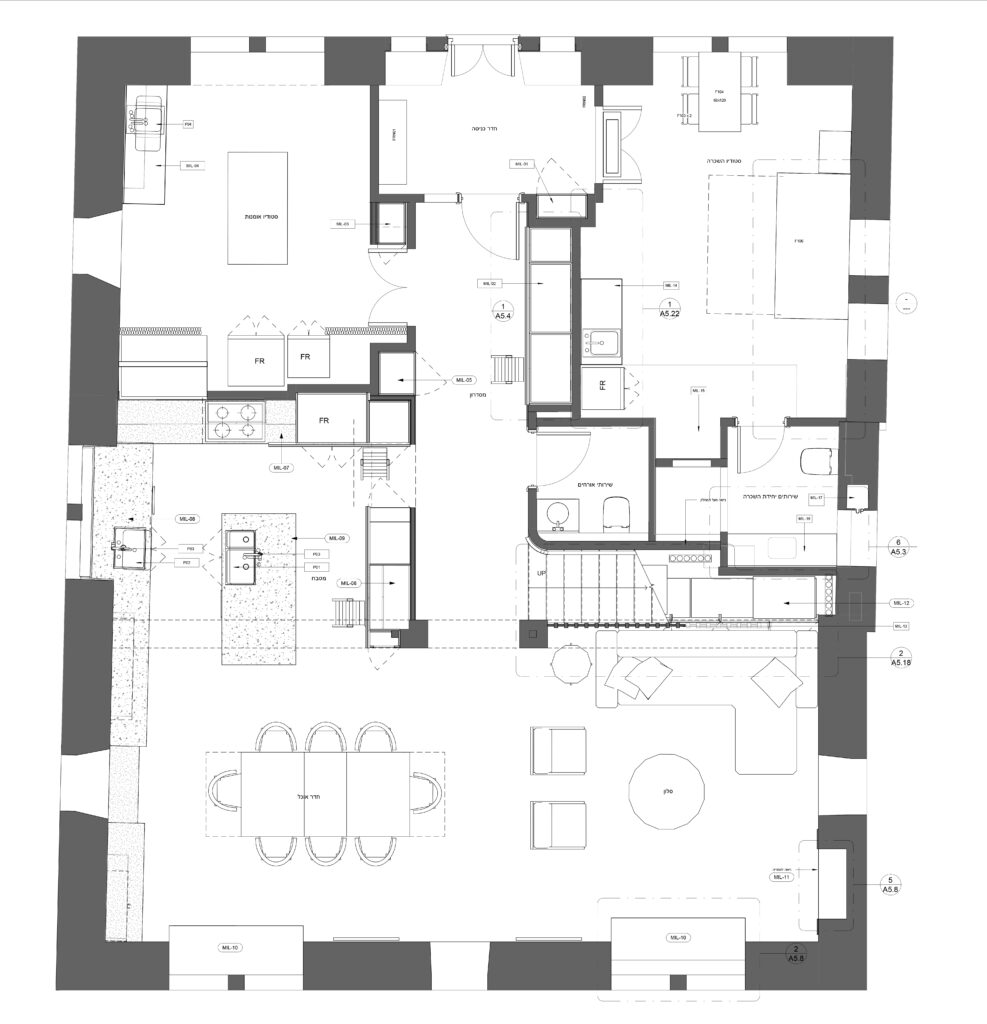

My role was very hands-on. I was supposed to do interior design at home. We worked together with the architect Shari Har Tuv. But gradually I started to study the architecture of the space, because I know the needs of the family better. While working in the Revit program, I saw many possibilities: additional storage spaces, niches, changes in the attic and ceiling.

Can you tell us about the process of changing the layout? What was the most challenging part?

Simcha: So the main challenge was the two original stone columns in the hallway. They determined the width of the corridor, and it ended up being very wide, about two meters, while the kitchen, on the other hand, became too narrow. I was wondering if we could move the stone column if it’s actually standing on steel? If you move the stone but the load is still carried by the steel, structurally it should work. We asked the engineer, and he said no. Three times “no”. But then we spoke to the contractor, and he said, “Yeah, that should be possible.” And when the contractor talked to the engineer, suddenly it was okay. So we narrowed the hallway and expanded the kitchen and the studio. That allowed us to create a proper island, a full coffee station, and much better circulation. And it’s been tested: we had about eight to ten people cooking here at the same time during my sister’s birthday!

Let’s talk about the kitchen. It feels like the heart of the house. Why was it so important?

Simcha: We’re a religious family and we host a lot, especially Shabbat meals. The kitchen had to function on many levels. Kosher requirements mean two sinks, separate storage, lots of dishes: everyday, Shabbat, dairy, meat, Pesach. Storage becomes critical. The kitchen was a collaboration with our architect, Shari, who laid the bones. Then I made many changes. I used Miro all the time – I cannot live without that program. We had a 3D mockup, and my mom and I discussed everything: what she had had in her old kitchen, the measurements, what needed to fit where, the heights, the ergonomics. Some choices were tough. The carpenter pushed for certain decisions and sometimes my mom and the carpenter overruled me. But I fought for specific proportions – the depth of the wall unit, the size of the island, and the walkway clearances.

Rebecca: In our old house the kitchen was tiny and chaotic. Here, it’s calm. I can cook, people can sit, talk, be together. It changed our daily life!

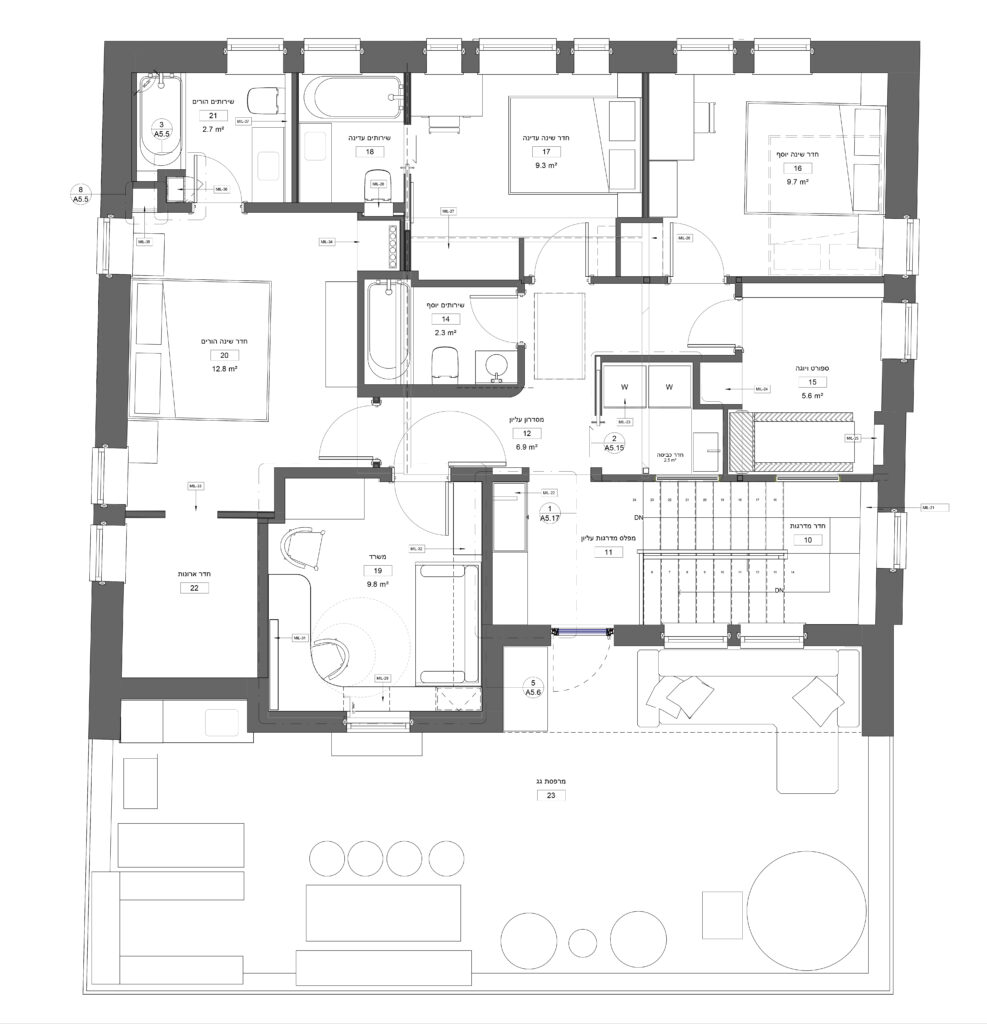

Storage is everywhere, but it’s almost invisible. Was that a conscious strategy?

Simcha: Completely. I’m obsessed with storage. I hate visual noise. Every wall is an opportunity. Every column is an opportunity. Even constraints like structural columns become storage if you think differently. For example, in the kitchen we had a steel column that had to stay. On one side I made deep drawers; on the other side, shallow ones, because the stone column behind it couldn’t be touched. It looks clean, but it’s very calculated. Everywhere you look are hooks, shelves, niches, built-ins, IKEA hacks. Not everything is expensive! Sometimes you make budget-friendly solutions look elevated. Like the upstairs chill area: IKEA units, repainted, combined with leftover color samples. It works perfectly.

Rebecca: Simcha notices things I don’t. I just know that everything has a place now. That’s life-changing.

Art plays a major role in the house. How did it influence the design?

Rebecca: The art didn’t lead the design – it followed it. That’s the joy of having a painter in the house. I see my house as a gallery. I’m willing to sell works straight off the wall.

Simcha: Only after we had moved in did I realize how many artwork my mother actually had. Rolls and piles of paintings. We’d pull something out and I’d say, “This is amazing.”

Let’s talk about the living room. The placement of art, the height, the perspective – it all feels very intentional.

Simcha: The large painting in the living room works almost like a window. The perspective is low, so when you are sitting, it feels like you’re looking into another space. That’s why we hung it lower than usual. Suddenly you’re not in Jerusalem – you’re somewhere in another room, in another space, green and open. It changes the feeling of the room completely. The funny thing is that we didn’t plan it. We bought the couch and the pillows first, and only later found the painting. But when we hung it, everything clicked: the colors of the shelves, the textiles, the wall. It brought the whole composition together.

Rebecca: Most of the works are mine, but they come from very different periods. In the old house, they worked one way; here they work differently. Space changes art.

How did the idea of exposing the stone wall come about?

Simcha: When you remove the plaster, you discover the original stone underneath. It’s not as “beautiful” as exterior stone, but it has an amazing texture and my mother wanted to expose it. Some of the neighbors exposed stone on all the walls, all around the house, but for me it felt too heavy. I only wanted one wall, as an accent, and the kitchen felt like the right place for that.

We also kept the original numbers on the stones. It’s similar to what was done in the Mamilla project: the builders numbered the stones so they could put them back in the exact same position. Keeping those numbers became part of the story of the house.

One of the most memorable spaces is the yellow guest bathroom. Can you tell us about it?

Simcha: That bathroom is very personal. The floor tiles came from another part of the house – original to the home and over 100 years old. We pulled them up carefully, and although many broke, we had just enough to cover that space. It became a puzzle. Once we decided to use them there, everything else followed.

The palette came from the tile. My mom mixed the yellow paint herself – two colors together. I got obsessed over the trims, the alignments, the lighting. We redid some parts more than once.

Rebecca: It reminds me of my aunts’ tiny bathroom in New York, full of character, layered, a little eccentric. It’s not Israeli at all. People go in there and stay much longer than they need to.

Color seems to be something you both understand deeply.

Simcha: Color is relative. There’s no absolute. The same color will look different next to another material, another light source. That’s why you need to test things in context.

Rebecca: I’m not afraid of color, but I also don’t want it to shout. A house should hold you, not overwhelm you.

What about the upstairs chill zone, it feels like a floating space. How did you come up with the second floor and attic solutions?

Simcha: The architect originally planned a dropped ceiling and enclosed loft above the stairs. But when I saw the space in 3D, I realized there was a lot of unused volume. We eliminated the room, created a double-height space, and added a skylight. That completely changed the feeling of the upper floor.

Originally there was supposed to be a loft. But in one space I realized an entire area above would become dead space. So instead, we created a lounging, yoga room, a reading area with light from both sides. You can host many people who can scatter around the house and still find private corners.

During the renovation, were there moments when you felt unsure about certain decisions?

Rebecca: Of course. When you are inside such a long and intense process, doubt is unavoidable. There were moments when everything around me was dust, noise, and chaos, and I asked myself whether we were making the right choices. But I trusted the vision and I trusted Simcha. I knew that even if something felt uncomfortable in the moment, it was part of a bigger picture.

Simcha: Doubt is actually an important part of the process. If you don’t question your decisions, you’re probably not paying enough attention. Some of the most significant choices were made very late, after the construction had already begun. Proportions, wall positions, storage depths. The ability to adapt and not freeze the design too early was crucial.

You mentioned that you moved into the house before everything was finished. Why was that important?

Simcha: Because drawings lie. Living in a space teaches you things that plans never will. You suddenly understand circulation, how light behaves at different hours, where clutter naturally accumulates, where people tend to stop or gather. Many of the best solutions were born only after we were already living here.

Rebecca: It allowed the house to grow organically. Not everything had to be resolved from day one. We gave ourselves permission to live with questions.

Did daily routines influence the space in unexpected ways?

Simcha: Absolutely. For example, certain storage solutions became more important than we had anticipated, while others mattered less. Morning routines, hosting patterns, even where people drop their bags – all these micro-behaviors shape space more than big gestures.

Rebecca: I noticed how much calmer my days became. Cooking, painting, hosting – everything slowed down. The house absorbs stress instead of amplifying it.

How does the house support creative work today?

Rebecca: It gives me permission to work and to stop working. My paintings live with me; they’re not separated into a studio. I can see them in different lights, different moods. Sometimes the house itself becomes part of the work.

Simcha: From a design perspective, it’s a testing ground. I see what works, what ages well, what doesn’t. Living inside your own design is the most honest critique.

You clearly designed for real life, not just for photographs.

Simcha: Absolutely. Good design comes from collaboration between designer and client. People often don’t know how they’ll live in a space until they live there. That’s why we left things unfinished and adapted.

If you had to choose one guiding principle behind the house, what would it be?

Simcha: Designing for how people live, not how they want to be perceived.

Rebecca: I want people to walk in and feel that real people live here. That it’s alive.

Interview by Nadia Kraginskii and Olga Goldina for DI CATALOGUE

Contacts:

Simcha Shore: simchashore.com

https://www.instagram.com/_itssimplysim

Rebecca Shore: www.rebeccashore.com